EUREKA! WE HAVE FOUND IT:

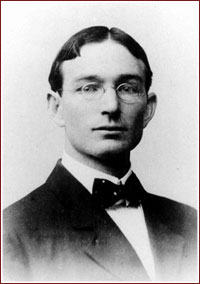

WILLIS D. WEATHERFORD (1875-1970)

Founder of the YMCA Blue Ridge Assembly

“It is not the negro that is on trial before the world, but it is we, the white men of the South.”

– W.D. Weatherford

Traveling through the Blue Ridge Mountains by horse and buggy in 1906, Weatherford, the Student Secretary of the International Committee of YMCAs for the South, sought a permanent location for his student training sessions. He stopped two miles from Black Mountain between two steep, forested ridges, climbed a tree to survey the surrounding land, and from its top branches exclaimed, “Eureka, we have found it!”

The enterprising educator then raised half a million dollars to finance the construction of the YMCA Blue Ridge Assembly on the site.

Left: Willis D. Weatherford in 1920 on a trip to Mount Mitchell.

As Student Secretary, Weatherford’s travels to college campuses across the South during the Jim Crow era made him acutely aware of race relations. In 1908, he met with six men–four of them African American–to discuss “what college men of the South might to do better conditions.” The consensus was that Weatherford should prepare a textbook to be used by the YMCA.

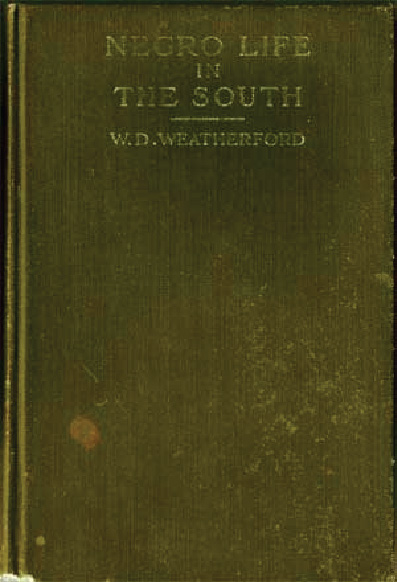

In 1910, Weatherford published the widely distributed Negro Life in the South, the first volume in a series of books on Southern race relations. Volumes 2-4 were authored by Booker T. Washington.

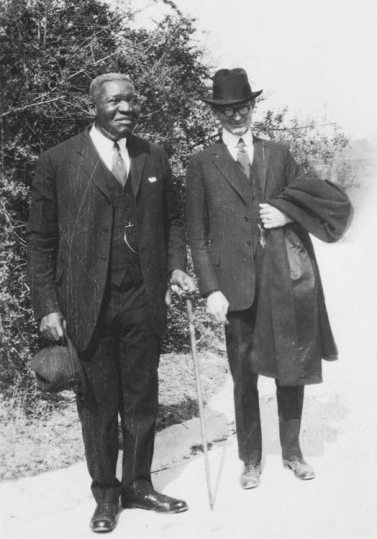

Right: Robert Russa Moton and Dr. Weatherford, ca 1920. At the time, Moton was principal of the Tuskegee Institute and successor to Booker T. Washington. Photo courtesy of the Blue Ridge Assembly.

“We know the negro as a hired servant in our homes. We know Aunt Mary, who cooks our meals, who waits on our table or acts as housemaid in our homes. We know John, the butler, or the coachman, or the gardener. We know the day laborer who cleans the street or hauls the coal, or runs the grocery wagon. We know one or two negro men who…have positions as mail carriers, and perhaps we know half a dozen negroes who, because of skill and hard work, have entered the list of skilled employment. But all of these we know only in their work. We do not know their thought; we do not know their religious life; we do not know their home life.”

-Weatherford, from Negro Life in the South

In subsequent years, Weatherford organized interracial conferences on social issues attended by college students, faculty, clergy, and politicians from both the North and the South.

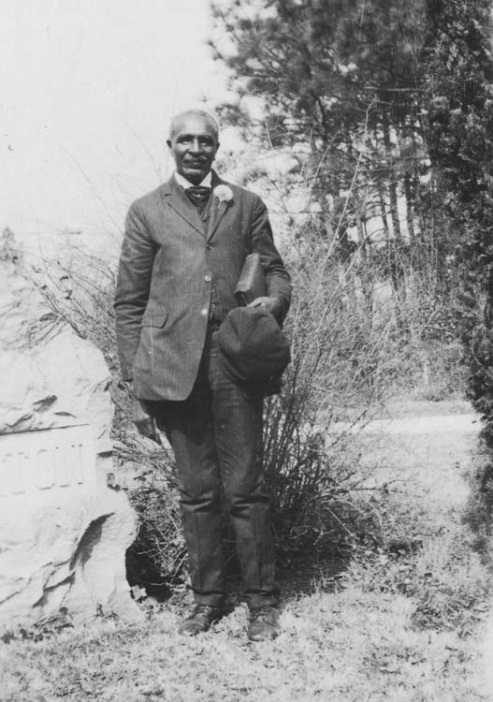

Left: George Washington Carver visited the Blue Ridge Assembly in 1923 and 1924. Carver’s stay was the first recorded racial integration of Blue Ridge Assembly. Photo courtesy of the Blue Ridge Assembly.

In 1964, Weatherford reflected on the inroads initiated during his tenure and the legacy of Blue Ridge Assembly:

“We were doing something about the whole race problem. [Slavery] left a dirty mark on Southern life … We set ourselves deliberately to break that prejudice down. Blue Ridge has been one of the forward-looking institutions…willing to take a step forward, even though sometimes it might not be popular…we knew it was right.”

Weatherford also envisioned the Blue Ridge Assembly as a place for college students to develop strong work ethics while taking courses on Christianity. In the summer, when conference-goers attended the Assembly, college students would clean rooms and wait tables as part of Weatherford’s emphasis on service.

In April of 2003, Anne Weatherford, daughter-in-law of Willis D. Weatherford, sat down with an interviewer Emily Lower and talked about her father-in-law’s legacy. Listen to excerpts from the interview below.

In 2014, Robert E. Lee Hall, the architectural centerpiece of the Blue Ridge Assembly grounds, was renamed Eureka Hall in tribute to Weatherford and his pursuit of social justice.