Throughout the mid-1800s, one-room school houses dotted the Swannanoa Valley, but these schools only served white students. It wasn’t until around 1886, when John Myra Stepp, who was born into slavery, provided funds to establish the Flat Creek Road School that the first school in Black Mountain for African-American students opened.

Little else is known about the Flat Creek Road School; however, the March 3, 1899 issue of The Asheville Register reported that, though three schools served the 331 white students in Black Mountain, “the necessity for erecting a suitable house for the negroes prevented the committee from having any school taught for the negro race this year (in Black Mountain).”

By the early 1900s, however, there was at least one school serving Black Mountain’s black students. In 1912, Buncombe County School superintendent A.C. Reynolds indicated that the Black Mountain Colored School teachers received $35/month salary, and taught five months of the year. It is uncertain whether Reynolds was referring to the Flat Creek Road School or a new two-room log school building that had recently been constructed on Cragmont Road.

The Black Mountain Colored School appears to have operated out of the log structure until 1942 [Note: according to Mary Othella Burnette, the rock school – Clearview – was built prior to 1937 when she entered first grade there.] when a larger stone structure replaced it. According to Sylvia Stepp Carpenter, who attended the stone school in first and second grades, it was always referred to as “the old rock school.”

“I went to the old rock school and we had first, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh grade,” Carpenter said. “First, second and third was together, fourth and fifth was together, and the sixth and seventh was together. We didn’t have but three rooms and we had the potbellied stoves. And the outhouse way down.”

In 1950, the school board began taking construction bids on a modern brick building to replace Black Mountain’s aging stone structure. Plans for the new building contained five classrooms, a kitchen, cafeteria, toilets, an office, a store room, and a boiler and fuel rooms. If funds sufficed, the plans also included the addition of an auditorium.

“I was president of the local PTA. We had teas and we raised enough money to (buy) all of that equipment up there in the kitchens. I don’t remember what we did about the table, but everything in that kitchen and that dining area we paid for. It was about $3,500. Now, that really belonged to us. But see, after integration came, the state came in and took over (and) took it all out. I don’t know what they did with it, but we paid for that.”

In November 1953, The Asheville Citizen reported, in an article about plans for improving area schools, “Carver children must now stand outside waiting to go on stage in dramatic productions, (so) new dressing rooms were recommended. The (plan) said that the patrons of that school have already gone into debt by $1,850 to provide cafeteria equipment.” The next year the only recommendation for improvement to Carver was “paper holders needed in toilets.”

The same year, on May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously declared separating black and white public school students unconstitutional, thereby overturning the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision allowing segregation. However, the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education ruling did not provide any method for desegregation, and the follow-up 1955 decision provided states only with the guideline to desegregate “with all deliberate speed.”

In Buncombe County, limited desegregation did not occur for nearly a decade after the first ruling, and the measures put in place earlier were merely attempts to forestall the full integration mandated by the federal government.

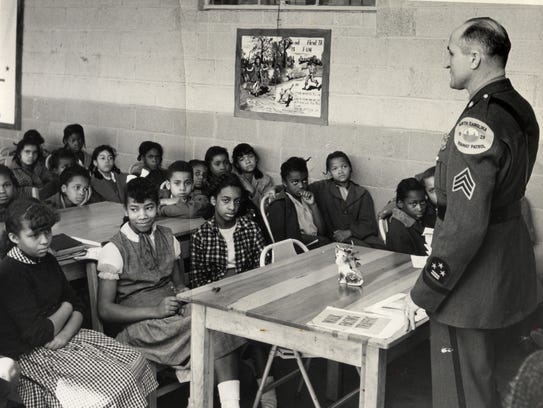

In the meantime, Carver’s teachers and staff put in extra effort for the school’s children. A March 1955 article in The Asheville Citizen-Times reported on the activities of Mrs. Robert Pinkston’s first-grade class at Carver. “Students … thought that milk came from bottles and that bacon ‘came from the store.’ However, that was before Mrs. Pinkston began a study of animals that gave food. Now the students are interested in cows, pigs, hens, sheep, squirrels and rabbits. They have made pictures and clay models of the various animals, and also of the food which they provided. As a close to the unit, they plan a field trip to a dairy where they can see milk, cream, butter, cheese, and of course ice cream.”

Another Asheville Citizen-Times article from October 1958 noted, “It is no secret that students in Carver School, Black Mountain, are fond of gingerbread, and it also is known that Mrs. Margaret Gragg, lunchroom manager at the school, has her own secret recipe for making the treat. … She serves it to the children cut in thick squares, because Mrs. Gragg insists that gingerbread must be cut in thick pieces to taste good.”

The article continued, “It is whispered that some of the gingerbread may be on sale at the food bar during a Halloween carnival to be held this month at the school.”

Despite impending school integration, in 1962 Carver School went through an extensive renovation that included the addition of a library, classroom, kitchen, teachers’ lounge, extra restroom facilities and remodeling of the school’s cafeteria.

The following year, the county gave black families with children in grades 1-3 the option to apply for their children to attend formerly all-white schools. A year later, the option opened to 4-6 grades.

That year, however, only 22 of 150 county school black students in grades 1-8 (out of 20,000 total students) applied to transfer to Haw Creek Elementary, a formerly all-white school. Only 12 of the black students were admitted, (school overcrowding was cited as the reason). Unhappy parents filed a lawsuit against the county schools, and in April 1965 the court ruled that “General overcrowding … cannot justify the … exclusion of Negro pupils when the much more numerous white pupils are all accommodated.”

Daugherty remembered of the beginnings of integration in Black Mountain “… the school superintendent … came out. We had a meeting and he said that we could integrate or we could stay (at Carver). Well, we said would integrate for this reason: our children were not getting the same education as the white children were getting. That’s why we voted to go ahead and integrate, (but) there was no more drama classes or anything like that done after that.”

At the start of the 1966-67 school year, Carver Elementary consolidated with Black Mountain’s primary and grammar schools. The Asheville Citizen reported on Sept. 2, 1966 the consolidation was ultimately caused by “a federal court edict that requires youngsters residing in a particular school attendance area … go to school in that area.” Besides Carver, the only other school serving black children had been Shiloh Elementary in the southern part of Buncombe County, making for long commutes for some students.

Sixty-five former Carver Elementary pupils enrolled at Black Mountain Elementary in 1966 and another 25 at Swannanoa Elementary, thereby closing Carver. Shortly after the beginning of the school year, all principals at the consolidated schools reported that the integration was working out, with no disciplinary problems noted.

“As far as I could tell, and my children were in school at the time, there wasn’t any real friction; it seems to me that it went along pretty well. There weren’t any police incidents,” Harriet Styles, one of the founders of the Swannanoa Valley Museum, reported.

There was never a high school in Black Mountain for black students. To continue their education, students had to attend school in Asheville. Lillian Lytle Logan remembered, “my aunt (Lizzie Wells) drew up a petition. … She collected money to get us a bus to go to Asheville to school after we finished the seventh grade. And I mean fifty cents, dollars, and all this until they got enough to get a bus.” In eighth grade, Logan attended Hill Street School in Asheville, followed by Stephens Lee High School for ninth.

The petition, dated Aug. 24, 1935, reads, “We, the patrons of the Black Mountain Colored School, want our children to continue their studies in High School, and in order to do this we need a bus to send them to Asheville. The Siperintendent (sic) of Public Instruction of Buncombe County informed us that it took $800.00 to buy a bus and that the State would furnish $600.00 of the amount and the County $50.00, provided we would raise $150.00.” Many Black Mountain citizens, white and black, contributed to the fund.

Styles recalled that “five black men in the Swannanoa/Black Mountain community … went together and bought (the) bus. One of the men drove the bus so that black students could go into Stephens-Lee High School.” Black families sending their children to school in Asheville also “had to pay the difference in school tax between what the city people and the county people paid, which I thought was very unfair,” Styles said.

When discussing possible integration of the high school 30 years later, the major point in favor of sending black Black Mountain students to Owen High School rather than bussing them to Stephens-Lee ended up being the absurdity of the bus passing right by the front doors of Owen (which was located where the middle school is now) on its much longer journey into Asheville.

(Anne Chesky Smith is director of the Swannanoa Valley Museum.)