by Katherine Cutshall

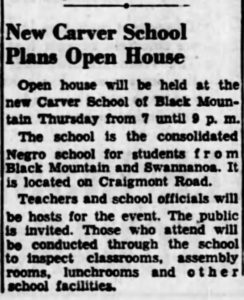

Built as an elementary school for African-American students in the early 1950s, the Carver School off Cragmont Road in Black Mountain has lived many lives and seen many changes. Tucked into a corner of Black Mountain, Carver Community Center has seen everything from elementary school musicals penned by award-winning artist Billy Edd Wheeler to a stage for a federal court battle promoting speedy desegregation in the Jim Crow South. How did this unassuming building play host to this whirlwind of changes over the course of just over 50 years?

In the 1960s African-American parents in Buncombe County were out of patience. The County school board’s plan of gradual integration was moving at a snail’s pace and placing their children at schools that were unreasonable distances from their homes. Originally, the county planned for integration to be gradually implemented ending in the 1967-1968 school year. However, frustrated parents filed a federal lawsuit that ultimately sped up the County’s proposed plan. Prior to the desegregation of Buncombe County Schools, there existed only two elementary schools for African-American children in rural Buncombe County. Most black students were bused to segregated schools in the Asheville district. Carter Elementary was built in 1951-1952 to serve rural eastern Buncombe County. After a federal court battle that pit parents against the Buncombe County school board, forced integration finally merged the school with Black Mountain Elementary two years earlier than originally planned, in 1966.

For the next ten years the relatively new school building found little use. For a few years the building sat vacant after a $17,000 renovation performed just before desegregation. Buncombe County Schools discussed the idea of leasing the building to Asheville-Buncombe Technical Community College, however, that plan never came to fruition. By 1968 the Mills Chapel Baptist Church was leasing the space as a community center for homecomings and wedding receptions. However, by 1975 the building was in a bad state of disrepair and needed renovations to ensure the county’s investment remained intact. By that time, allowed to sit open and unattended, the school remained a shell of its former self. At a school board meeting in May of that year, it was recommended that the school be repaired and the county explore installing an open concept school at Carver – partly to ease congestion at Black Mountain Elementary.

The idea of an open concept school quickly became popular and parents from across Buncombe County endorsed the idea. A group of parents in Black Mountain, led by Gay Currie Fox, began hosting a study group to explore other open concept schools across North Carolina to educate themselves and others about new trends in education. The group toured schools in Lenoir, Charlotte, and Asheville’s own Newton Elementary School. An exploratory committee was established by the Buncombe County Board of Education, and by December 1975 the board voted unanimously to approve taking applications for the school in January for the 1976-1977 school year.

Carver took applications from children across Buncombe County, however, the majority of interest came from students in the Owen district because the county did not provide transportation to the new school. Like many charter schools today, students were selected via a blind lottery system; their applications placed in sealed envelopes labeled “boy” and “girl” and chosen every other one until their capacity was reached.

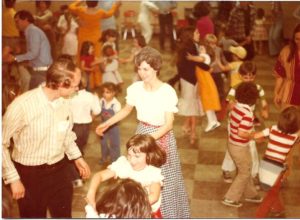

Unlike most typical schools, Carter relied on an open-concept educational model, allowing children a more self-guided learning experience. In a letter to parents in the Black Mountain News, the school emphasized that “Each activity is designed for the needs and abilities of the child and therefore, learning becomes a joyous and challenging part of his life.” In a similar press release to the Asheville Citizen-Times, the school also stressed tenants like openness, creativity, volunteer participation in the classroom, and multi-age classrooms as part of a “renaissance in theories” for education in the 1970s.

Certainly, many of those who attended Carter or who had children there praised the school and its educational model. Famed singer and songwriter Billy Edd Wheeler was a major proponent of Carver Optional School, writing along with his wife, Mary, an advertisement for the Asheville Citizen-Times entitled “Carver School Offers Challenge” citing all of the reasons one ought to enroll their child at Carver. Wheeler was a very involved parent, he even donated his creative services penning two musicals for the school, The Star Wars Encounter and All God’s Critters. Both shows received rave reviews from the local papers and conveyed themes of friendship and environmentalism.

Before long, the optional school began to struggle. Enrollment at the school began to drop off, and the Buncombe County Schools Superintendent N.A. Miller began eyeing the school for closure in a time when the district was going through a period of new building and consolidation. One idea was to move the optional school into another elementary school that had space. The school PTA came together to fight the decision, asking for a yearlong study. However, by 1987 the study had not been completed and Carver was closed for good. The 63 students who remained at the school were transferred to the schools closest to their home.

Almost immediately after the school’s closure concerned citizens began meeting about what ought to happen with the Carver School property. By 1989 Carver was purchased by the Town of Black Mountain for use as a multipurpose community building. The town had high hopes to utilize the building as a “model community center.” The first organization to reside in the building was Children and Friends preschool. Since then the building has been home to the headquarters for the Town of Black Mountain Parks and Recreation which continues to host various group activities and classes and provides space for the Swannanoa Valley Montessori School to operate inside the center’s walls.

This post was written using sources from the Swannanoa Valley Museum & History Center.