Prior to the American Revolution, Western North Carolina was a frontier occupied by the Cherokee, the largest group of Native Americans in the Southeast. In the mid-18th Century, the Cherokee numbered 36,000 and controlled 140,000 square miles from the Ohio River to Alabama.

Throughout the colonial period, white settlers continued to advance west, encroaching upon Cherokee territory. In 1766, provincial Gov. William Tryon entered negotiations with the Cherokee to extend the boundary of the western frontiers of the Carolinas into Cherokee hunting grounds. Tryon mounted a personal military expedition to engage in the talks. The Cherokee were flattered by the governor’s visit and deemed him the “Great Wolf of North Carolina.”

The Cherokee Boundary, signed on July 13, 1767, called for the removal, by Jan.1, 1768, of white settlers west of the boundary running north to south from Virginia to South Carolina and required traders west of the line to obtain a license. Following geographic features, the boundary ran from the Reedy River, south of Greenville along the border between Greenville and Spartanburg counties to the top of Tryon Mountain; it also followed the crest of the Blue Ridge to the New River in Virginia. The treaty proved difficult to enforce.

Ever since the infamous 1622 attack on Jamestown, colonists feared Indian raids. With tensions strained on the eve of the Revolutionary War, colonists suspected the Cherokee of colluding with the British. The Declaration of Independence even remonstrated the British for inciting borderland insurrections.

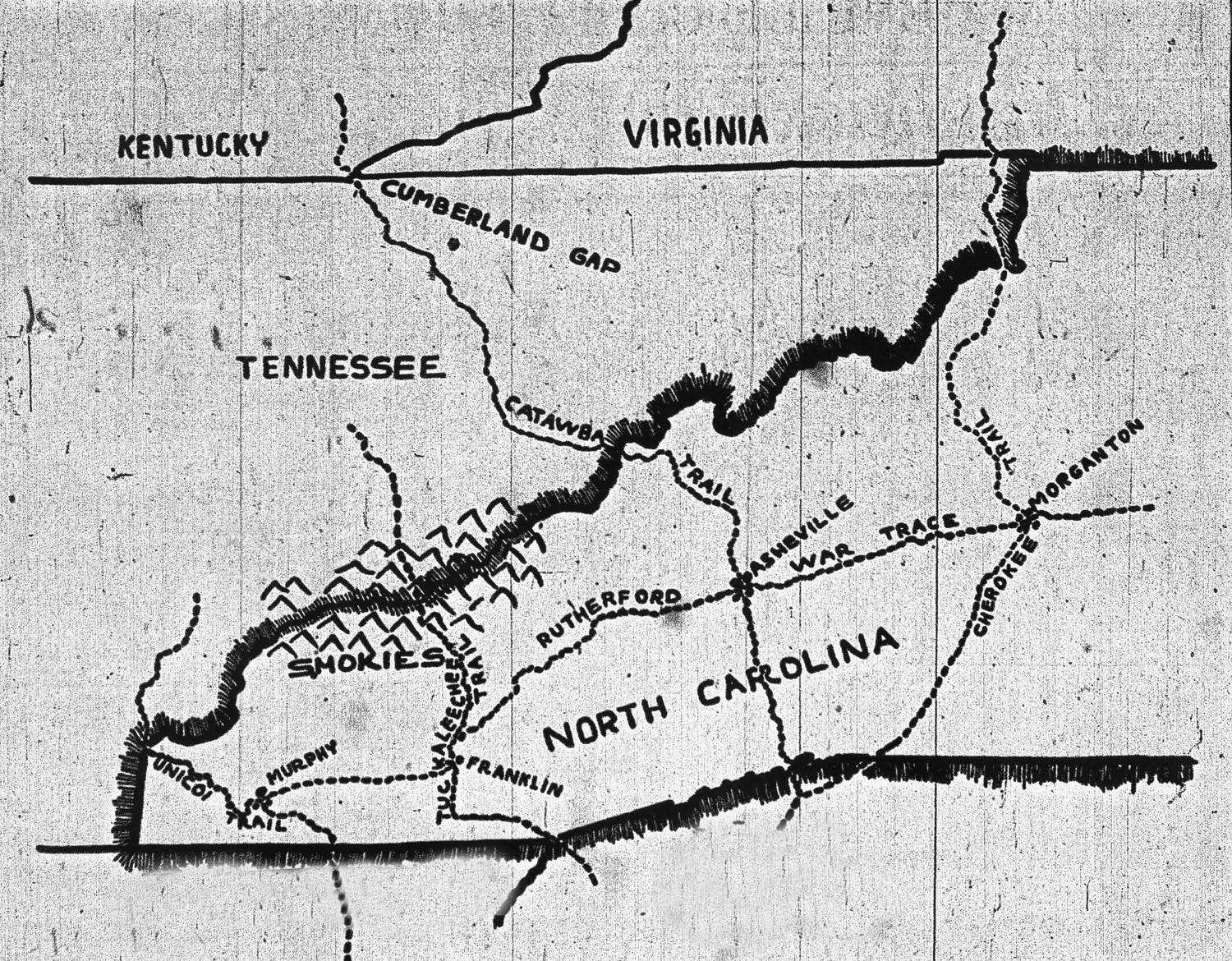

As a result, in September 1776, Irish-born, middle-aged, recently appointed brigadier general Griffith Rutherford led 2,400 white men and Catawba Indians, Cherokee foes, from Davidson’s Fort (today’s Old Fort) against the Cherokee in an attempt to punish the Cherokee for allying with the British. They destroyed more than 50 villages – including sacred council houses – and plundered livestock and burned acres of crops. The brutal raid, known as “Rutherford’s Trace,” has been compared to General William Tecumseh Sherman’s Civil War march across the South.

The militia crossed the Blue Ridge east of Black Mountain and followed the Swannanoa River to present-day Biltmore Village before crossing the French Broad River behind what is now the Asheville Outlets. From there, Rutherford led his men west to Jackson and Macon counties, destroying between 50 and 70 Cherokee towns with their “scorched earth” policy.

Rutherford’s Trace was lasting blow to Cherokee domination. Hundreds of Cherokee refugees risked starvation during the following winter. Rutherford ordered another militia raid against the Cherokee in November 1776 led by Capt. William Moore. Many of his men fought in the 1780 Battle of Kings Mountain and following the war settled in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee, lending their names to many counties and towns, including Rutherford, Sevier, Shelby, Lenoir, and Buncombe.