PALACES FOR THE PEOPLE:

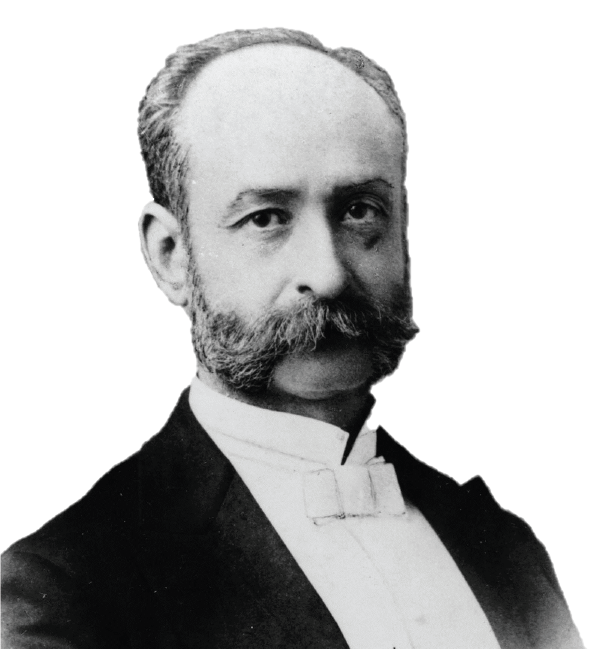

RAFAEL GUASTAVINO (1842-1908)

Spanish Master Builder known for creating vaulted tile domes across the U.S.

“Here was a man who emphasized the benefits of building with stone and tile—of making nothing but fireproof buildings, but because of the expediency and cheap cost…he made his home out of wood.”

– Helen Johnson, Christmount Assistant Director

Immigrating to the US in 1881, Spanish master builder Rafael Guastavino quickly changed the architectural landscape in America with his “cohesive construction” technique, a refinement of a centuries-old Mediterranean architectural method for spanning spaces with tile vaults.

The technology used multiple layers of thin ceramic tiles bonded with thick mortar between each layer. The resulting vaults were inexpensive, lightweight, interconnected spans, which were much thinner than traditional stone vaults and departed radically from American reliance on timber framing.

Guastavino Company vaults and domes can be seen across the nation at landmarks such as the Boston Public Library, Grand Central Station, and Ellis Island.

Right: A view of the vaulted tiles ceilings designed by the Guastavinos at the Ellis Island Registry Room. The tilework was added in 1918, 18 years after the room was opened. Photo credit Chensiyuan.

In 1894, Guastavino was pulled south to design part of the Biltmore Estate in Asheville. While in the area, he began to purchase tracts of land in Black Mountain to build his own grand estate, Rhododendron.

Left: The tile ceiling of the indoor pool at the Biltmore Estate in Asheville was designed by Guastavino. Photo credit Warren LeMay.

Guastavino’s home, known to locals as “The Spanish Castle,” was a depature from the typical Guastavino style of building. The wooden, 25-room structure was always a work in progress as remembered by Francesca’s maid, Florence Ownbey Plemmons:

“For the first few years the first floor was occupied by farm horses until a barn was built for them. After the horses were taken out, the first floor was remodeled into nice rooms for the family,” which included two kitchens, a large dining room, and a billiard room. “The second floor consisted of eleven rooms. First, the chapel room. Mr. Guastavino was a devout Catholic. He went into the Chapel to pray each morning before eating his breakfast. Across the hall [from the Chapel] was a music room with all kinds of musical instruments. He was the finest musician I ever saw in all the years I have lived.”

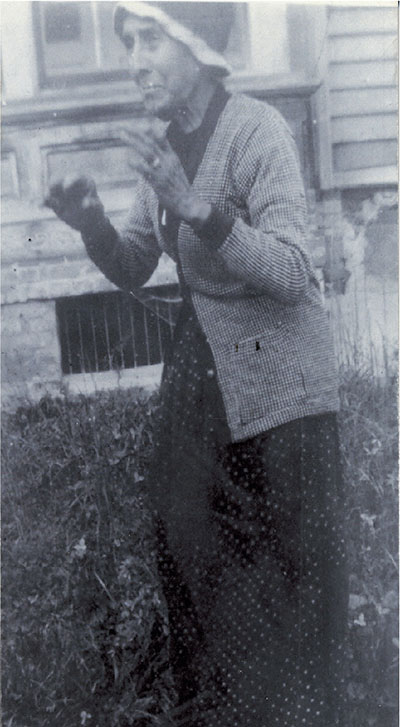

FRANCESCA GUASTAVINO

(1859-1946)

“She was a native of Mexico, a small, dark complected woman with coal black hair that touched the floor when she was standing. Surely her hair was her glory. She was a bit peculiar to be a rich woman. She did not like nice clothes or jewelry. She didn’t wear any jewelry except her wedding ring. She like to dress like the poor mountain people, with patches on her clothes.”

– Florence Plemmons,

Francesca’s maid

After her husband’s death at the age of 65, Francesca, once a young socialite, became a recluse.

“At the time of his death she had the big clock in the tower above the house stopped. She would never allow it to run again; it was a symbol that, for her, time had stopped.”

-Rafael Guastavino IV

Before his death in 1908, Guastavino’s final project was a collaboration with Richard Sharp Smith on the design of the Basilica of Saint Lawrence in Asheville. The Basilica also serves as Guastavino’s final resting place, housing the crypt in which he is entombed. Today, much of the historic Rhododendron Estate is now a part of the campus of Christmount Christian Assembly in Black Mountain, where the ruins of the Spanish Castle are still visible.

Right: Photo credit Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.