by Anne Chesky Smith

Nestled in the Swannanoa Valley of western North Carolina sits a winding Tudor-style country manor house. Known as “In-the-Oaks,” the 24,000 square foot home was built in the early 1920s for Franklin Silas Terry, the first vice-president of General Electric, and his second wife – and first cousin – Lillian Estelle Slocomb Emerson. The couple were well-known around western North Carolina for their festive parties uninhibited by the confines of Prohibition.

Originally spelled “Intheoaks” and named for the oak leaf entwined in the Slocomb family’s coat of arms, the manor, located just 15 miles down the road from America’s largest home, George Vanderbilt’s Biltmore House, boasts many of the same features as Biltmore – an indoor swimming pool, bowling alleys, and a wine cellar – but sees far fewer annual visitors.

The similarities between the two estates are not surprising. Frank E. Wallis, who worked with Richard M. Hunt in New York, and spent two years making drawings for the Biltmore Estate, designed In-the-Oaks, and Richard Sharp Smith – Biltmore’s supervising architect – was hired to design the recreation wing addition in 1923.

The similarities between the two estates are not surprising. Frank E. Wallis, who worked with Richard M. Hunt in New York, and spent two years making drawings for the Biltmore Estate, designed In-the-Oaks, and Richard Sharp Smith – Biltmore’s supervising architect – was hired to design the recreation wing addition in 1923.

The similarities between the two homes do not end there. The 80-acre property included a 3-hole golf course, putting green, stables, and an extensive natural landscape designed by the same man who landscaped the Biltmore property and New York’s Central Park – Frederick Law Olmstead. At the time, the meticulously landscaped estate allowed for 360-degree views of the surrounding mountain ranges from the second floor of the house. Now, surrounded by rhododendrons and shrouded by oaks and maples, the home seems to be miles into the wilderness – though it parallels Interstate 40 as it passes the Town of Black Mountain.

Unlike Biltmore, the house is unimposing, molded to fit the rolling landscape, and though it boasts 67 rooms, it appears to only be two levels, when, in fact, it is four. In a 1994 interview, Terry’s niece, Marion Perley Casstevens, summarized the difference between the two homes, “Biltmore was built to show-off. This house was built to have a good time.”

And, have a good time they did. The Terry’s were known for their parties. And the most interesting aspects of the home were constructed specifically not to be seen. Built during the Prohibition Era, the Terrys included many safe-guards in the home to protect their guests–and their expensive liquor collection—from nosey revenuers.

Hidden behind a trick panel in a main hallway is a dumbwaiter, which even if discovered, would appear empty unless the officers attempted to pull up the dumbwaiter. The space was designed to mimic similar secret English closets used during the Reformation to hide Catholic priests.

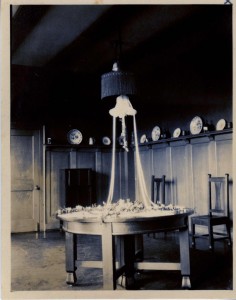

But the real parties were held in what was known as the Dutch Room. Built to resemble a Danish tavern, the room – located partially below ground—is still concealed behind two large doors in an oversized frame, which softened the party noises from the rest of the house. The centerpiece of the room – a blue and white Delft tile fireplace – monopolizes the far wall and once warmed a large bearskin rug on its hearth.

Mr. Terry often held late-night card games in the Dutch Room because its opaque leaded-glass windows concealed the room from prying eyes. The built-in wet bar was supplied from the estate’s secret wine cellar.

From inside a Dutch Room closet, Mr. Terry could release the closet’s false back with a hidden latch to reveal a few shelves holding a couple inexpensive bottles of liquor. But much like the dumbwaiter, this was merely meant to trick anyone investigating into not looking further.

For those who knew its secret, the shelves would move aside to reveal a locked sliding iron door. Behind the door were slots to hold 744 bottles of liquor. Each bottle was meticulously catalogued by Mr. Terry with its name, date, and cost. Mentioning the wine cellar, Casstevens remember Mr. Terry having liquor delivered in boxes marked “books,” and remarking that he “really believe[d] that everyone should get drunk at least once a year.”

Though their estate was spectacular, the Terry’s were much more than just their lavish home. Lillian, born in Fayetteville, North Carolina, in 1880, had fiery red hair and a personality to match. She was known as a first-class hostess, and made history in 1920 as the first woman to drive an automobile to the top of Mt. Mitchell – the highest peak in the eastern United States.

Her first husband died in 1909. After moving back to the United States from Paris with her young daughter – who would one day become a dancing sensation – at the outbreak of World War I, Lillian began to plan the construction of In-the-Oaks with her cousin, and close correspondent, Franklin Terry. In 1920, construction on the home began. The same year, Franklin Terry and his first wife, Grace, divorced.

In 1878, as a high school student working as an office boy in a small electrical manufacturing company in his hometown of Ansonia, Connecticut, Franklin Terry sat in on a meeting about electric lighting between the plant’s owner, William Wallace, and Thomas Edison. Their conversation inspired Terry and rather than attend college, he stayed on to manage Wallace’s company.

Over the next 40 years, Terry became a pioneer in the electric lighting industry – most notably developing a longer-burning incandescent light bulb. Eventually, with the understanding that his small company, based out of Chicago, could not continue to compete with the large corporations like Westinghouse and Thomson-Houston, he established a conglomerate of small companies under the auspices of the National Electric Lamp Company (NELA). NELA was absorbed by General Electric in 1912. In 1923, Terry was elected its vice-president.

As an industrialist, Terry was ahead of his time. He conceived the idea for America’s first industrial park in Cleveland, Ohio. Besides hosting an array of leisure-time activity spaces for employees – tennis courts, a library, baseball fields, a swimming pool, and a bowling alley – the complex served both men and women and was free from smoke fumes and other disturbances generally associated with industry at the time.

Terry was also well known for some of his philanthropic work. During World War I, Terry established a fund to aid French children orphaned by the conflict. The organization sent money for food, clothing, and housing to the young people and also provided aid to help the orphans obtain higher education. Terry personally “adopted” 57 children, with a total of 625 orphans receiving aid through his program overall.

In 1923, despite his busy work schedule with NELA in Cleveland and General Electric in New York, Franklin and Lillian tied the knot in New Jersey and then relocated full time to Black Mountain to oversee construction of their estate.

The couple only had three happy years in the home before Franklin died of a stroke on August 2, 1926. Lillian continued to live at the estate until her death in an automobile accident in April 1954. The home was left to Lillian’s daughter, who donated the estate to the Episcopal Diocese of Western North Carolina as a retreat center in 1957. Montreat College purchased the property in 2001 and maintains it for classroom and athletic facilities today.