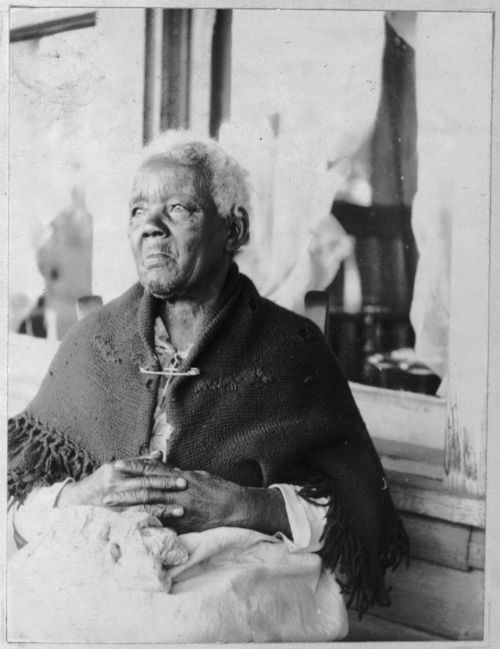

Photograph from Library of Congress, WPA Writer’s Project

By Anne Chesky Smith

Master’s brother, he said, “William, how old is Aunt Sarah now?” Master William looked at me and he said, “She is getting nigh onto 50.” That was just a little while after the war. -Sarah Gudger

When Sarah Gudger told this story in 1937, her interviewer, Marjorie Jones, might have supposed for a moment that that Gudger was referring to The Great War that had ended almost 20 years before, but Jones would have soon realized her reason for the interview—Gudger was a former slave—and remembered turning 50 right after the end of the Civil War, more than 70 years earlier.

In the 1930s, in an effort to support writers during the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt established the Federal Writer’s Project, under which the Slave Narratives employed writers from around the country to seek out over 2,300 former slaves and record their personal memoirs.

Besides Bills of Sale recorded at the County’s Deeds Office and census records, there is little official documentation of the slaves who lived in the Swannanoa Valley, and almost nothing that records more than their first names and ages. Thus, Sarah Gudger’s account of her enslaved life near the Swannanoa Valley helps those of us who live here now to understand a little more about what life might have been like for an enslaved person in the valley.

In September of 1816, Sarah Gudger was born on a large plantation owned by the Hemphill family near Old Fort. Her father, Smart Gudger, took his family name from his owner, Joe Gudger, who owned property on the Swannanoa River near Oteen.

Sarah spent the first years of her life working for Andy Hemphill. When Andy died, she was willed to his son, William, who would remain her master until she gained her freedom after the end of the war. Sarah remembered Andy and his wife with fondness, saying, “Missie used to read the Bible to us children before she passed away.”

But Sarah was not fond of William and his wife. “Old Boss he sent us out in any kind of weather, rain or snow, it never mattered. If the Ole Boss or the Old Missie see us [resting] they would yell, ‘Get on over hear you black thing, and get your work out of the way.’ And, Lord, honey, we knew to get, else we get the lash. They didn’t care how old or how young you were, you never too big to get the lash.”

Sarah recalled working from the early morning until late into the night chopping wood, working in the fields, hoeing corn, carding wool, and spinning yarn, being fed only cornbread and molasses, and sleeping on a pile of rags in the corner.

Often she would wait until everyone was asleep and risk sneaking out, walking two miles barefoot in the snow, to eat cornbread with meat and milk at her auntie’s house.

But despite the hardships she experienced, she was thankful that William never sold any of the enslaved people from her plantation. On William’s other plantation she remembered the times the speculator would come.

“All the slaves would be in the field, plowing, hoeing, singing in the boiling sun. Old Master he come through the field with a man. They walked around just looking, and everyone knew what that meant. They didn’t dare look up, just worked right on. Then the speculator would see who he wanted. He talked to Old Master, then they slaps the handcuffs on him and took him away to the cotton country.”

Sales would separate mothers from children, husbands from wives, with no notice. And despite the threats of harsh beatings, many would try to make their way back to the plantation, back to their families. Sarah said, “Oh, man Lordy, my old Boss was mean, but he never sent us to the cotton country.”

But even though none of the enslaved people from Sarah’s plantation were sold to cotton country, Sarah’s mother was sent away to the Hemphill’s Reems Creek plantation when Sarah was a teenager. Years later, when she found out her mother had died, she asked permission from William’s wife to go and see her body before she was buried. His wife replied, “Get out of here and get back to your work before I wallup you good.” Sarah returned to work in tears. Over 100 years later, at 120 years old, the Asheville Citizen published a brief quote by Gudger. Sarah said the only thing she had left to do was “to join [her] mother in death.”

At the end of the war, when she gained her freedom, Sarah spent another year with the Hemphills and then left to go live with her father and stayed with him for the rest of his life.

In 1937, Sarah Gudger lived with distant cousins in South Asheville, walking with the aid of a crutch. When she died a little over a year later, at 122 years old, the Amarillo Globe reported, “Aunt Sarah died yesterday as she has said she would – ‘propped up in bed takin’ things fair and easy ‘til the old marser calls me away.’ She was believed to be one of the oldest persons in the world. Until slightly more than a month ago when she became too feeble to ‘git aroun’ much,’ she was very active. She learned to write her name under tutorship of Works Progress Administration instructors of the adult education program.”

To read Sarah Gudger’s interview in its entirety consult Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writer’s Project available online through the Library of Congress. This article was written with information gathered from the Swannanoa Valley Museum in Black Mountain.

For more in-depth information on Sarah Gudger’s life, see Museum Assistant Director Katherine Cutshall’s interactive online exhibit, Sarah Gudger’s Journey to Freedom.