THIS WAS MY VALLEY:

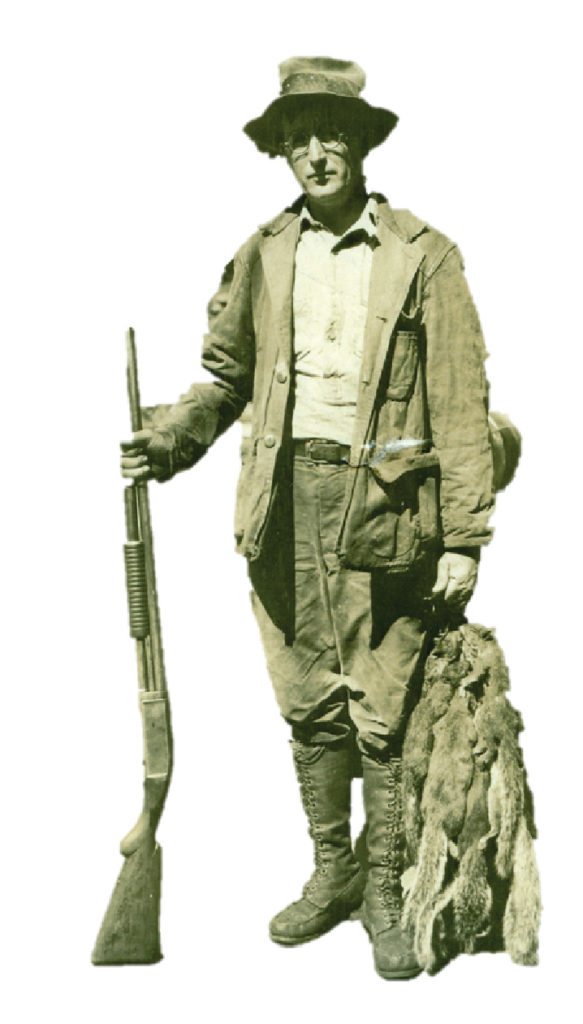

BASCOMBE BURNETTE (1882-1966)

One of many forced from his home to provide water for Asheville

“It surely grieves me to look up old North Fork at the works of man, it’s all gashed up by modern civilization…Such is life. There is nothing we can do about it.”

-Bascombe Burnette, December 30th, 1954, Black Mountain News

In 1800, Bascombe Burnette’s grandfather, Frederick Thomas Burnett, Sr., and his wife, who was known as “Granny Else,” stopped under the shadow of the great Black and Craggy mountain ranges and declared they would go no farther west than the North Fork of the Swannanoa River. Though the land was rocky, the game was abundant, and the family built the first log cabin in the valley near the spot where, 100 years later, City of Asheville workers would bulldoze and shape the land into a 1,309-foot earthen dam for their new watershed, taking the land using eminent domain.

Left: Bascombe Burnette

“I was born under the shadows of Craggy Garden…many happy hours have I spent under the azure blue of…its turbulent trout streams and eternal hills…many jars of cream, butter, and eggs in stone jars sunken in the huge poplar log…it being the only refrigeration to us at the period. A great many lived principally by gathering wild ginseng and other herbs sold to Hines and Wilson at Cooper Station, now Swannanoa. Of course some of us had hogs that lived on chestnut and acorns and other mountain resources…” – Bascombe Burnette

Many other people migrated to the North Fork Valley over the next century, including NC Civil War Governor Zebulon B. Vance. But the Burnetts remained a central force in the development of the North Fork Valley from a wilderness to a community that, at its beginning, had a population competing with the City of Asheville.

Amongst other things, Burnetts organized and preached at the first church, taught at the one-room schoolhouse, and served as Justices of the Peace, magistrates, and constables for the area.

But in the early 1900s, in the words of Thad Burnett, “the north end of the North Fork Valley was selected [for Asheville’s water supply], the land condemned and fenced. Notices were nailed to the trees containing a new word to the mountaineers, ‘No

Trespassing.’ The trails were closed. The saddened community, bewildered, wandered away. Thousands begged for permission to pass through the forests again, but were refused.”

However, several Burnetts found quite ingenious ways to continue to visit the land that was now closed to the public. Will and Bart Burnett became the first wardens to patrol the property. Their father, Fate, who loved to hunt, approached Asheville’s mayor with a concern. He told the mayor about a number of deep pools within the watershed property where black bears would wallow. Appalled at the thought of bears muddying the city’s water, the mayor gave Fate the exclusive right to chase all the bears out of the watershed by whatever means necessary.

Today, the North Fork Reservoir, also known as the Burnett Reservoir, is part of the Asheville Watershed, which is the fourth-largest watershed run by a city in the United States. The Burnett Reservoir provides over 15 million gallons of high-quality water per day to the Swannanoa Valley and Asheville.

Right: Looking toward the North Fork Reservoir and the upper reaches of the Swannanoa River Valley. Photo courtesy of WNCOutdoors.

Chimneys, graveyards, and the foundations of homes can still be seen in parts of the North Fork Valley, a reminder of the valley’s historic community and the Burnette family’s legacy.

Left: The remains of Col. John Kerr Connally’s lodge in the North Fork Valley. Photo credit Joe Standaert.