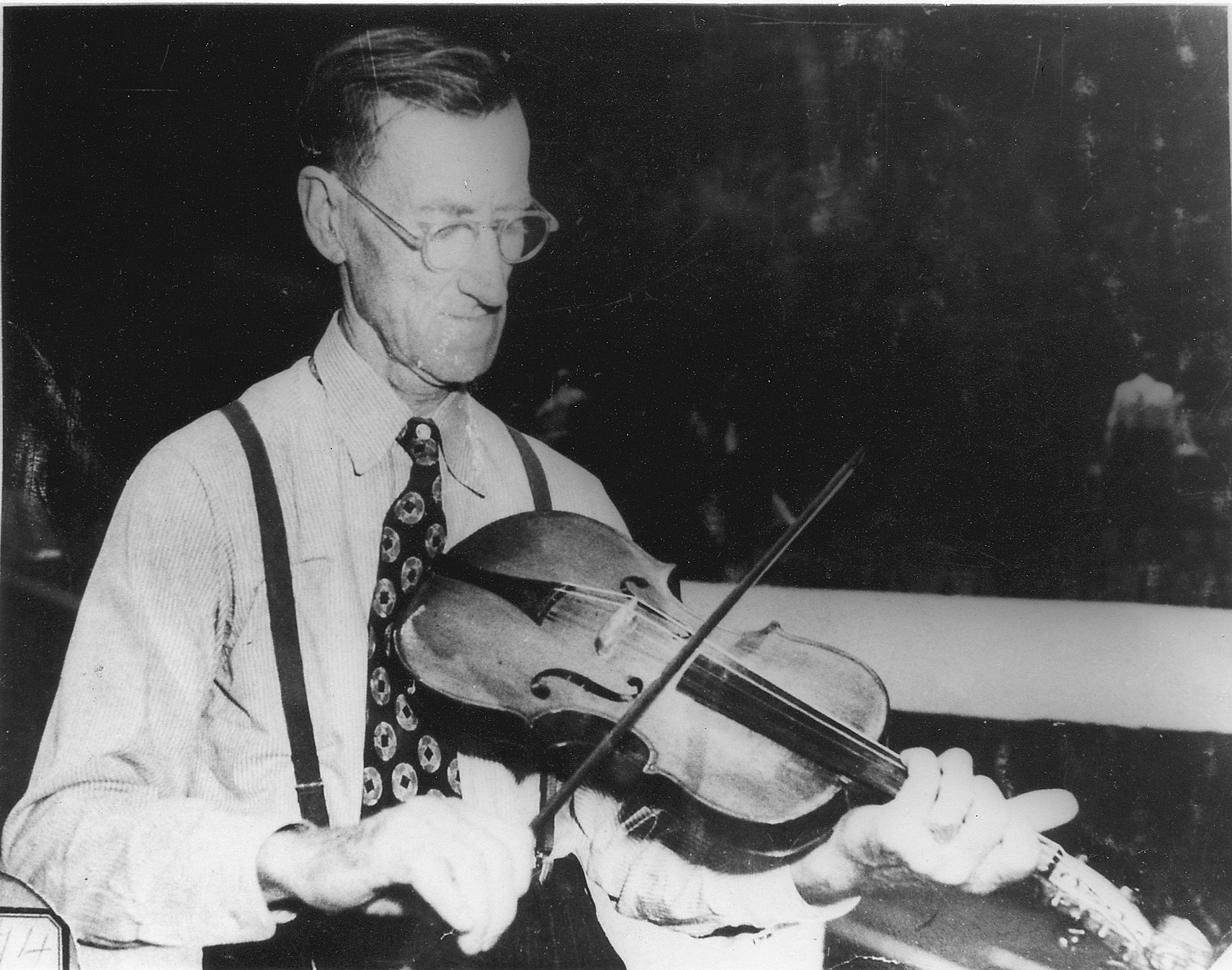

FIDDLE A POSSUM OUT OF A TREE:

MARCUS MARTIN (1881-1974)

Champion fiddler with songs in the Library of Congress

“Don’t ask me how it come to me. I don’t know for sure. I guess it was talent, if you would call it that. Just come naturally. All my ancestors were musicians, see, and I guess I took it from them.”

– Marcus Martin, Asheville Citizen-Times, 3/24/1974

By the mid-1800s, a fiddler could be found in almost every settlement in Southern Appalachia, including in Cherokee communities. Martin’s half-Cherokee father, Nathaniel “Rowan” Martin, taught him most of his repertoire and technique. Though Rowan himself never found acclaim as a musician, Martin remembered years after his father’s death that he “could play the sweetest you ever heard.”

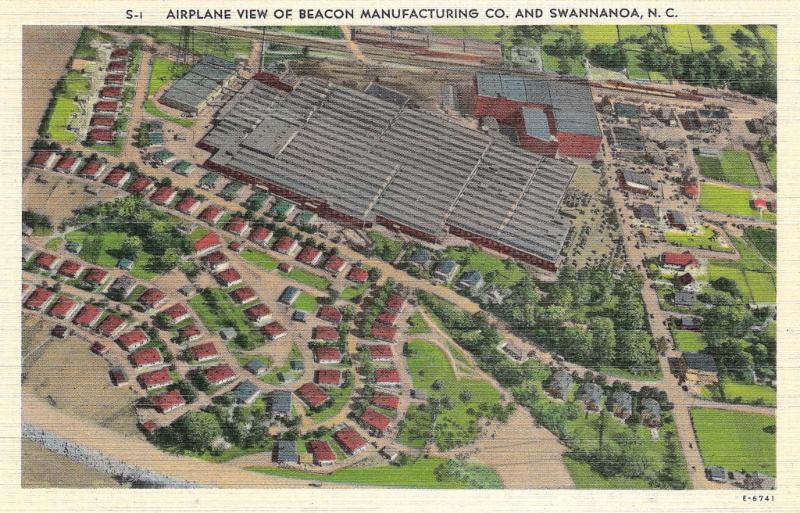

Martin began playing publicly in his youth, often fiddling tunes unaccompanied at square dances around Macon and Cherokee counties. Years later, he married Callie Holloway, a “good five-string banjo picker” herself, and they had six children — five boys and a girl. In the 1920s, Martin separated from Callie and moved with his boys to a quickly developing Swannanoa for a job at the Beacon Blanket Mill.

Beacon’s owner, Charles D. Owen, was fervently against unions, and he figured the best way to stop his workers from trying to unionize was to make sure they were happy (and dependent upon the mill not only for their jobs, but their housing and social lives as well). So, according to local legend, when Owen heard Martin’s masterful fiddling, he offered him a job on the spot. Martin, then, after work hours, would give live performances for others living in the mill village.

“I’m a fiddler you know not a violinist. What I do play is old time stuff. I don’t know a thing about music.”

marcus martin

“He could fiddle a possum out of a tree. He could fiddle all the bugs off a sweet-potato vine. He could fiddle the heart right out of your throat.” – John Parris, Asheville Citizen-Times, March 24, 1974.

He was often asked to play at company picnics, square dances, and even dances Grove Park Inn.

A few years after the Martins made the move, Bascom Lamar Lunsford began organizing the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville. Martin became a favorite of Lunsford’s and opened the festival for many years with the traditional tune “Grey Eagle.”

Left: Lunsford (left) plays banjo accompaniment for a flat foot dancer at the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival.

In the mid-1940s, recordings of many of Martin’s songs were made on acetate discs and placed in the Library of Congress. Still, Martin claimed he “didn’t know a thing about music.” In reality, he knew hundreds of songs and even won the title of “Champion Fiddler” at the 1949 North Carolina State Fair.

“Won it again in 1950 and never tried for it again. I figured I could just sit back and let somebody else have a chance.” – Marcus Martin

Martin still spent most of his time working as a watchman at the Beacon Mill to make ends meet. In his spare time he made fiddles and mountain dulcimers to sell, always carefully carving a scroll at the end of each instrument. He passed on his carving skills to his sons, many of whom became well-known carvers within their lifetimes.

Left: Carved figurines of musicians playing together, by Wayne Martin. Courtesy of D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections, UNCA Asheville.

Today, old-time fiddlers still try to match Martin’s style by listening to his recordings. Many of his old-time tunes have been adapted by modern fiddlers, including some of his most unusual songs such as “Lady Hamilton” and “Jenny Run Away in the Mud in the Night.”