by Melanie English

The “Spanish Castle,” the estate of architect Rafael Guastavino, just south of Black Mountain. Examples of the internationally renowned architect’s craftsmanship grace many of America’s most famous Beaux-Arts landmarks, including the Boston Public Library, Grand Central Terminal, Grant’s Tomb, the Great Hall at Ellis Island, Carnegie Hall, the Smithsonian, and the U.S. Supreme Court, as well as the Biltmore Estate and Basilica of Saint Lawrence in Asheville.

Born in 1842 in Valencia, Spain, Rafael Guastavino y Moreno abandoned a promising musical career to pursue architecture, which he studied in Barcelona alongside modernist Antonio Gaudi. Guastavino was bestowed the title mestre d’obres meaning “master builder,” analogous to an architectural engineer for his revival of a Catalan masonry technique of layering thin tiles to produce lightweight and fireproof self-supporting arches. The method may have been a region variation of Roman arches or introduced through the Islamic invasion in the eighth century. Guastavino was awarded high-profile commissions, such as Barcelona’s largest textile factory, but after his first marriage failed, he packed up his youngest son and immigrated to New York in 1881.

Language proved a barrier as Guastavino struggled to secure commissions, finally landing the contract for the vaulted ceilings of the Boston Public Library in 1889, from the prominent firm of McKim, Mead, and White. The library’s holdings included rare books and the papers of John Adams, and thus the architects were willing to risk awarding the commission to a relatively unknown foreigner because of his fireproof masonry. Guastavino created seven vaults for Renaissance revival building and rose in the nation’s attention. The commission led to projects in thirty-two states. His company, the Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company opened offices in eleven cities across the county and the company eventually received 24 U.S. patents.

As Guastavino’s reputation grew, George Vanderbilt commissioned him to supervise the construction of vaults at the Biltmore Estate, visible in the entrance vestibule, the Winter Garden, and the swimming pool. Guastavino relocated to North Carolina in 1891. In 1894, Guastavino started investing in land in eastern Buncombe County and across the ridge in McDowell County. Guastavino acquired additional acreage in 1897 and 1901, amassing over 600 acres, most of which was never developed. In 1895, he built a home for himself and his second wife, Francesca in a cove south of Black Mountain. The estate served as his primary residence for the last years of his life.

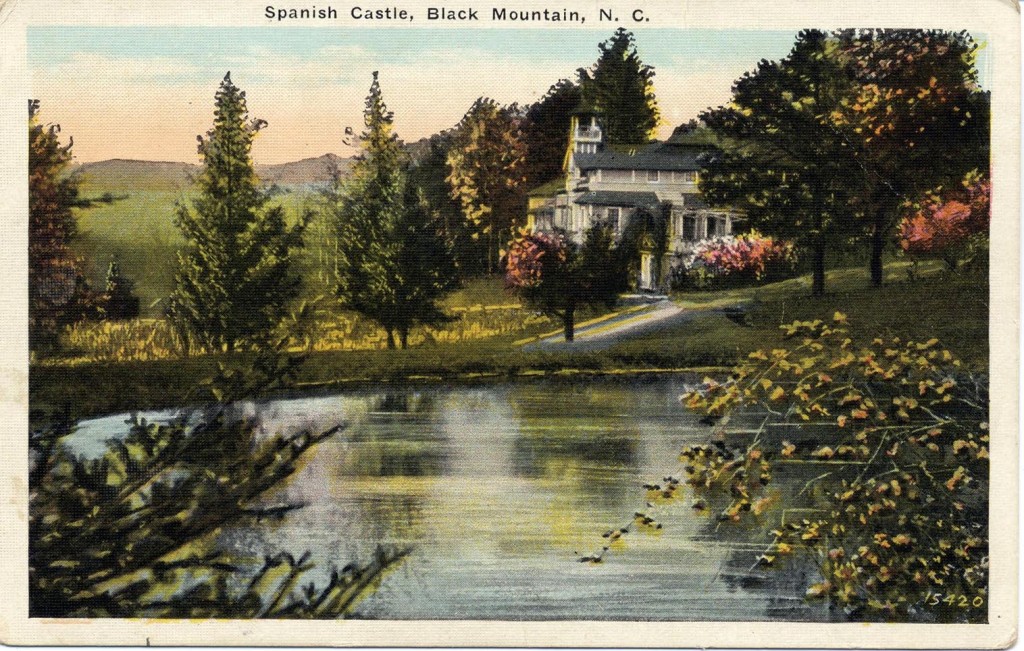

Situated on an east-west axis extending up into Brittin Cove and bounded by Lakey Creek to the south and N.C. Highway 9 to the west, “Rhododendron” was a ramshackle three-story white washed wooden house with a central bell tower. Through grander than local farmhouses, the house did not exhibit the cohesive construction technology that made the architect famous. Locals called the house the “Spanish Castle.” Guastavino did employ tile vaulting in the construction of a hillside wine cellar. He made cider from apple trees on the property. He had special bottles made, embossed with the estate’s name, and shipped cases of cider to friends and family during the holidays.

Guastavino continued his experiments with tile technology from the grounds of Rhododendron, taking advantage of North Carolina’s abundant clay and waterpower supplied by Lakey Creek and two manmade ponds. Guastavino built a gazebo overlooking the picturesque ponds. Although no formal landscape plans exist, the grounds show the influence of Frederick Law Olmstead, the designer of Central Park and the Biltmore Estate grounds. Like Biltmore and other area estates including Zealandia, Seely’s Castle, and In the Oaks, the romantic landscape design of Rhododendron took advantage of the fan-shaped valley and irregular terrain to create terraces ornamented by native hardwoods, evergreens, and flowering trees.

Guastavino built at least two kilns, one which still survives, complete with its 60 -foot tall chimney fully intact. The kiln could fire thousands of tiles at a time, including those used in the Basilica of Saint Lawrence, completed a year after Guastavino’s death in 1908. The proximity of the railroad in Black Mountain enabled Guastavino to run his business from the estate. Company letterheads from the turn of the twentieth century feature the Rhododendron’s address. Rafael Jr. took over the business following his father’s death and in 1910 executed one of the largest domes in the world for New York’s Cathedral of Saint John the Divine. Guastavino’s widow continued to reside at Rhododendron. Living as a recluse, she survived fire started by an old stove until her health declined and she passed away in 1946.

The dilapidated estate was razed in the late 1940s. Today, the brick foundations of the “Spanish Castle” are visible on the grounds of Christmount, a national retreat, camp, and conference center for the Disciples of Christ. The bell from the house’s tower was given to the Swannanoa Valley Museum. The museum also has a small collection of bricks and bottles from the estate, in addition to photographs depicting the estate. Christmount offers a walking tour and exhibit in the guesthouse open to the public year round. Click here for more information.